Author’s Journal

REMEMBERING LISA WARREN JOHNSON

June 7, 1944 to April 12, 2018

Lisa on her Wedding Day, May 1976

I doubt I will ever walk through a garden again without thinking of Lisa Warren Johnson. When I learned of her death on April 12, 2018, I wept for hours. The date of her death meant Lisa had not been able to finish her spring gardening, a task she looked forward to every year. Lisa had been working for a family who lived nearby as a nanny and tutor for their son. When Lisa didn’t arrive on time on the morning of April 9, the boy walked to her house. When she didn’t answer the door, Lisa’s student called his father, who entered the house, found Lisa unconscious in bed, and called 911. Lisa had suffered a massive stroke in her sleep; she died in the hospital three days later without regaining consciousness. Once we leave our childhood homes, the absence of a spouse or roommate increases our vulnerability to medical emergencies in the middle of the night.

My friendship with Lisa spanned fifty years. It began in June 1969 when Lisa came to my Boulder office to interview for a teaching position with Project Head Start. An East coast native born in Worcester, Massachusetts, Lisa had recently graduated from the University of Colorado at Boulder and wanted to make Boulder her permanent home. My Head Start office on Canyon Boulevard was located in a World War II Quonset hut which had been unevenly installed on a parcel of land designated to become a future park. Lisa arrived for her interview at this primitive muddy and weedy site wearing two-inch heels, a Laura Ashley dress, and white dress gloves. Her outfit conformed to the style rules which she had learned as a student at Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Connecticut, where Jackie Kennedy had also been groomed. Because decorum in dress had been all but obliterated during the 1960s, I made an attempt to put Lisa at ease by gently teasing her about her white gloves.

Seven months before Lisa’s interview, the Office of Child Development (OCD) had cancelled the Boulder Valley School District’s grant for Project Head Start after a government evaluation found a lack of parental involvement and an inadequate nutrition program. When I arrived from Northern Idaho to manage the transition to a parent-controlled non-profit corporation, the five centers (three in Boulder, one each in Lafayette and Louisville) were located in upscale Protestant churches. Food was transported from Boulder Valley school cafeterias to the church classrooms (where ninety percent of it was discarded). Looking for ways the teaching staff could build stronger connections with the families of Head Start children and increase parental involvement, I relocated the Boulder centers to low income neighborhoods. Lisa’s energetic enthusiasm for Head Start led her not only to agree to teach in one of the new experimental centers, but to live in one as well. Luckily for Project Head Start, it turned out that Lisa was more comfortable wearing polo shirts and hiking shorts than white gloves.

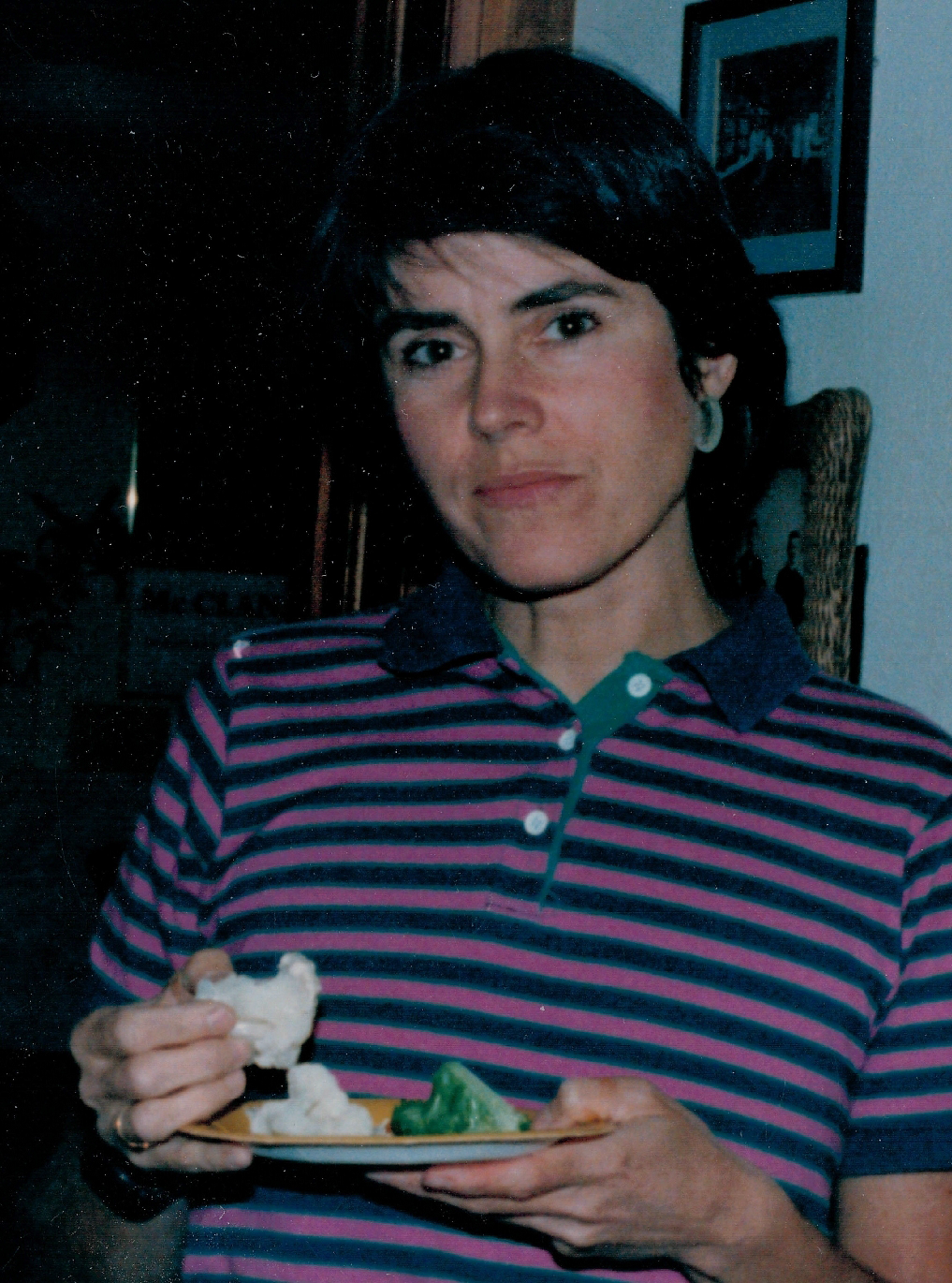

Lisa in Her Preferred Costume

Snacking on Raw Vegetables in 1973

Lisa went to work and live in the Goss Street Center, where in 1969 the Goss-Grove neighborhood population was still primarily low income Hispanic and black families. We transformed the main floor of an older Victorian-style house into classrooms and the neglected yard into a playground. The house had two small attic rooms; one became a bedroom for Lisa, the other a storeroom for supplies. All but two of Lisa’s fifteen (15) Head Start students lived within easy walking distance of the Goss Street Center. Funds previously needed for busing were instead used to hire a cook and the kitchen became a place where fresh and delicious culturally familiar food was prepared.

From her first day Lisa demonstrated phenomenal teaching skills. Soon many of her students began making their way back to the Goss Street Center after class ended, making Lisa’s role as resident teacher a 24/7 responsibility. The absence of respite was not the only challenge she faced. One day Lisa asked a parent-volunteer to retrieve an item from the attic storeroom. The mother, like most of the other Hispanic parents was a devout Catholic and she somehow spotted a packet of birth control pills on the top of Lisa’s bedroom chest of drawers. While in 1965 the Supreme Court had given married couples the right to use birth control, in 1969 millions of unmarried women in 26 states were still being denied access to hormonal birth control. Further there was considerable controversy about its use among Catholic clergy and parishioners. A major kerfluffle followed, which Lisa managed to survive by using the full array of social graces she had been taught at Miss Porter’s School.

Lisa was an adventurous traveler. At the end of her first year at Head Start, she asked me to care for her beloved classroom guinea pigs while she went into the wilds. The following summer, the guinea pigs returned to my house, along with a six-toed calico cat named Splotch who also needed room and board while Lisa traveled to Machu Picchu in Peru. Our friendship deepened when Lisa left Head Start to take a teaching position at Upland School, Boulder’s first alternative elementary school, where my daughter became her student. Eventually Lisa left Upland to take a teaching position at University Hill Elementary, followed by one at Eisenhower Elementary. From her first year as a teacher, Lisa had an innate sense of what interested young children. She filled her classrooms with her own carefully curated collections of arts and craft materials, musical instruments, supplies for science experiments, friendly animals, and favorite books. Each learning environment she created was more impressive than the last.

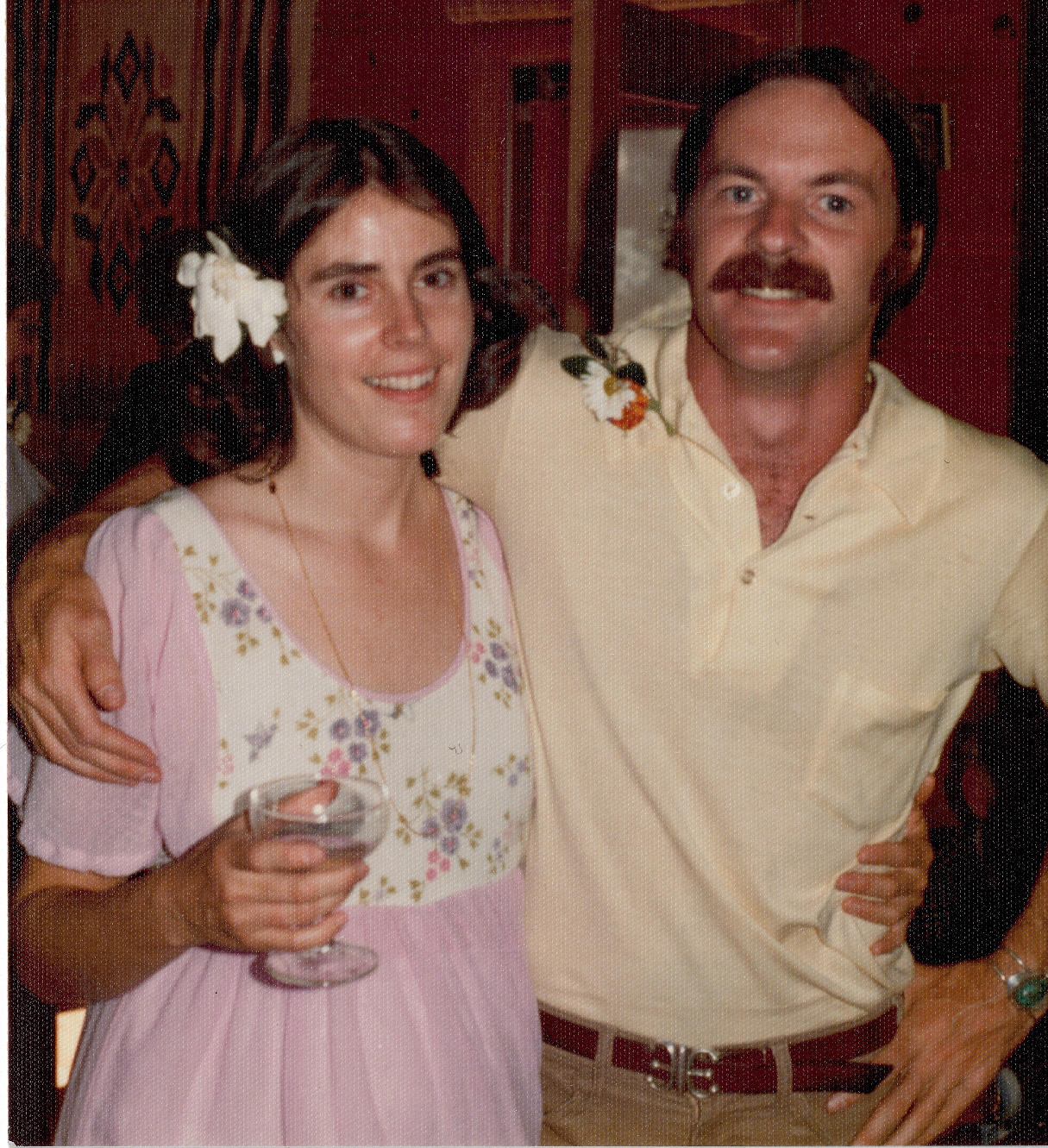

Lisa with her fiance

Steve Kent Clark August 23, 1975

In the fall of 1975, Lisa began making plans for her first and only wedding. She and Steven Kent Clarke were to be married in the spring. I can still see her on her knees planting hundreds of tulip bulbs in the flower beds bordering the large backyard of her home on 11th Street in anticipation of their May garden wedding.

Lisa’s 11th Street garden was a panorama of tulip perfection the day before the wedding, but heavy rain began to fall at dawn. By mid-morning, the rain showed no sign of abating. To create dry shelter for the wedding guests, we were forced to hastily remove all the furniture from her main floor master bedroom which overlooked the garden. I remember my husband Bob, who performed the ceremony, saying: “Into every marriage a little rain must fall.” More than a little fell that day and on others that followed. A son was born in December 1976, but in July 1978, Lisa and Steve divorced.

Lisa’s son, Alden F. Clarke, was named after her father and he became the primary focus of her life. He was an academic star, as well as an Olympic-level fencer, who graduated from Stanford University. Sadly, after Alden’s graduation from Stanford, a sudden onset of mental illness lead to his estrangement from Lisa and Steven. Still Alden remained Lisa’s highest priority until her death.

Lisa with her son Alden F. Clarke

Because Lisa shared a birthday with my mother, I found it easy to remember hers. For two decades we enjoyed a tradition of celebrating her birthday over lunch. After I began working as a management consultant, my travel schedule disrupted our easy connections. Luckily in May 2015, our paths accidentally crossed at a local gardening center. We caravanned in our separate Subarus to Vic’s Coffee Shop on North Broadway, where our reunion conversation lasted four hours. A few weeks later, we met again for lunch on Lisa’s birthday. Having revived our old tradition, we had lunch again in 2016 and 2017. In early December 2017, we had a long conversation over holiday tea and lemon cake in my living room. That afternoon, Lisa told me a secret story about how she had come to learn that squirrels have an incredible ability to endure freezing temperatures for long periods of time.

Ten days later, Lisa sent me an email.

I just about jumped out of my skin when I saw your book at Boulder Bookstore last week. I grabbed it right off the shelf. I can’t tell you how I’ve loved reading it, especially since I knew many in the cast of characters (including some of the cats), as well as the places and events and some of the story. I did miss reading about Ilona of Hungary, the asparagus fern and Emma Martinez… It’s lucky I still have your fudge recipe on a card in my kitchen drawer because it wasn’t revealed anywhere in the book!

Much Love and Congratulations, Lisa

Lisa Warren Johnson in foreground at

the Boulder Bookstore on Valentine’s

Day 2018 (Lisa is seated next to Patrice

Byrne and in front of Judy Reid,

Richard B. Collins, and Martha Armstrong.)

On Valentine’s Day 2018, Lisa surprised me by coming to a reading I did at the Boulder Bookstore. Regrettably, I didn’t know that would be the last time I would see her. A few days later she wrote me again: “I could have been a geneticist in another life!” Explaining that Part Two of Optimal Distance had peaked her interest in the new science of epigenetics. She also said how much she had enjoyed herself. “I had a long conversation with Patrice Byrne after your talk, and a shorter one with Judy Reid who was sitting behind me. I saw many familiar faces from the past who I heard about or met through my connection with you. I enjoyed that part of the evening very much.”

Still ignorant of her death, in early June 2018, I emailed Lisa proposing a date and place for her birthday lunch. When she failed to respond, I felt a vague sense of worry. But most of us become more reclusive as we age. I thought maybe Lisa was treating her justifiably reasonable blues with chocolate cake from Lucky’s Market. Or perhaps she had gone east to see her siblings, or was totally preoccupied with her research into epigenetics. Sadly, I did not know that she was already gone and did not learn of her death until June 21 when her obituary was finally published in the Boulder Daily Camera.

I loved Lisa Warren Johnson – her wonderful laugh; her persistent precision, and the many ways in which she made the world richer with magical teaching and artistic gardening. I was in awe of her ability to see the potential within each of her students, as well as her energetic search for any and all answers in her desire to help Alden. She had cross-species relationships with many animals and eagerly opened her arms to the most challenging kinds of travel adventures. I will miss her until my last breath. Blessings on her memorable soul.

Joan Carol Lieberman

Boulder, Colorado

July 2018

Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference

The circumstances of my childhood turned me into a life-long diarist after I discovered that writing alleviated loneliness and my fear of death. In 1998, I was inspired by Terry Tempest Williams’s book, Refuge, An Unnatural History of Family and Place, (New York, Pantheon, 1991) to submit a collection of my diary entries to the Bakeless Literary Prize because Terry was judging that year. I wanted Terry, who lost her mother and grandmother to the breast cancer, to know what a powerful impact her writing had on me. My submission, a collection of diary entries relating to my own experiences with breast cancer, was a kind of fan letter. I assumed Terry would receive a stipend for the time she spent reading, so that my amateur submission would not amount to an inappropriate imposition.

I was stunned when a letter arrived telling me that I was one of three finalists for the Bakeless Prize, and further, there was a consolation prize: an invitation to attend the 1999 Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference as a Bakeless Scholar. I accepted, despite the fact that I had absolutely no ambition to publish my autobiographical writing. I went because my husband Bob and I had already made a plan to travel to New York City to celebrate the first birthday of our first grandchild the week before the Conference.

Our granddaughter’s birthday party took place in Westchester County at Brook Astor’s Briarcliff Manor estate, a location that deserves it own story. A few days later Bob and I drove further up the Hudson to Wappingers Falls in Dutchess County to search for the grave of my paternal grandfather, Jacob Liebermann.. The only role Jacob Liebermann had played in my life was as an unmentionable missing man. My hunt was inspired by Helen Fremont’s book, After A Long Silence. After reading her story, I began to explore the scar tissue of the familial wound Jacob had inflicted almost eighty years earlier when he first betrayed his wife, before abandoning her, my father, and their three other children in Ogden, Utah.

Bob’s famous persistence finally located Jacob’s unexpectedly grand granite marker in Wappingers Falls City Cemetery. It read: Jacob Liebermann, born August 14, 1882 – died July 10, 1947. As I looked at the inscription I realized Jacob’s life had overlapped my own for five years. For a brief moment, I wistfully wondered if my paternal grandfather had somehow heard of my existence through some unknown familial grapevine.

In 1946, the year before Jacob Liebermann died of a heart attack outside Wappingers Falls at his roadside store and gas station on Albany Post Road, my father had driven my mother and me across America in his 1939 Chrysler. We had traveled east from Delta, Utah to his birthplace in Newark, New Jersey. On the return trip, we deliberately detoured to Niagra Falls, crossing the Hudson River at the Tappen Bridge, before we began following a parallel track north.

In a scene out of some poignant, frustrating movie, we unknowingly passed Jacob Liebermann’s roadside store and gas station. It is remotely possible that Jacob caught a glimpse of my father’s profile in the Chrysler’s window as we passed. If so, perhaps Jacob’s weak heart skipped a beat seeing the driver’s vaguely familiar visage. Jacob may have even seen my face pressed against the Chrysler’s high back window in search of permissible childish distraction since it was long before the restraint of car seats and seat belts.

When Bob found Jacob’s gravestone fifty-three years later, we took a picture, wondering what had happened to Jacob’s second wife, Emily. Her name was also on the stone, but only her birth date was listed: Emily Liebermann, born May 28, 1897. We decided she must have died and been buried elsewhere, perhaps after marrying again. Were she still living she would have been one hundred two years old.

After another day with family, Bob and I parted at LaGuardia Airport. He flew home to Colorado while I drove to Bread Loaf in Ripton, Vermont. Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference turned out to be an extravagant spa for my brain. As a Bread Loaf novice, I had mistakenly prepared myself to spend three weeks writing, interspersed with a few group meetings and joint meals. Instead, Bread Loaf was a marathon of readings and workshops–an elaborate banquet of stimulating analysis, new perspectives and rich language. I felt more alive than I had in years, even with the paraphernalia of cancer in my pockets. The only writing I did at Bread Loaf was to compose two letters home to my husband, the last of which included a prophetic dream about writers and readers.

Sunday, August 15, 1999, Birch Cabin at Bread Loaf

Dearest Husband,

Remember how I wanted to change my mind as we stood at the Hertz Counter in LaGuardia? “I don’t want to go; just take me back home with you, okay?” I was surprised to hear my own voice and syntax sound like I was ten years old, trying to persuade my father not to make me go away to camp. Well, I was going away to camp! I had my flashlight and warm coat. I had read those rigid rules about roommates and the not-so-subtle messages from Carol Knauss about the real risks of regression. It was entirely possible I was on my way to a disaster. As you waved goodbye from the Hertz bus, I started to cry. I was so discombobulated that I couldn’t find the rental agreement for the Hertz guard at the lot exit. The drivers in the cars behind me began blasting their horns and I didn’t know which way to turn. Already I was regressing.

You laughed at me after Bread Loaf staff wrote to request my photograph because I sent one taken eight years earlier. I can now assure you that I was already intuitively within the Bread Loaf culture! I have only been able to recognize about half the faculty from their photographs in the Bread Loaf brochure. So far, I think Clark Blaise has won the contest for the greatest distortion of time. Coincidentally, two nights ago, Blaise read from a forthcoming book about time. Ten hours earlier his wife, Bharati Mukherjee, had spoken so eloquently about acculturation and cosmopolitanism that I decided her husband was a lucky man. After Blaise finished, I thought she was a lucky woman. Like us, they are a perfect cross cultural match; much smarter though.

Another surprise: I expected to be the oldest camper at Bread Loaf, but I am not. Further, the conference is heavily populated by menopausal women–probably because they finally have time to write since they can’t sleep. In my creative non-fiction workshop, we have all paused and changed, except for one young male writer who calls himself “Sundance.” In his solo status, he is appropriately respectful, surrounded by women like the one he left home to escape. Sadly, he is too inexperienced to recognize us as valuable source material.

I thought Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference was a place where writers went to write. I was so wrong! Bread Loaf is more like a listening camp! There are lectures and readings all the time. In between there is training in social listening at serial cocktail parties and shared meals. I have been most challenged by some of the poets. I often feel unable to hold all their stunning similes due to my personal federal-sized deficit of estrogen. For this reason, today I almost didn’t go to the morning lecture by the poet Ellen Bryant Voigt. But luckily something tugged me out of bed.

Voight was crisp, on-fire with indignation about a critic’s recent assessment of Randall Jarrall as a mediocre poet and she launched into a remarkable exposition of Jarrall’s work. Voigt’s voice transported me back to Berkeley in 1961 when I stayed up all night writing an essay about a Jarrell poem in the dining room of the boarding house on Durant Avenue, while upstairs my hostile, narcoleptic roommate slept in our barely shared room. That poetry class was the only one I took in all those college years. By the time Voigt finished with Jarrall’s poem “Field and Forest” I was weeping for how I have wasted my life. I haven’t read a single Jarrell poem since I left Berkeley. I’ve been too busy.

Saturday night, Daniel Wallace, author of Big Fish, read a new short story, looking like a puffer fish, stuffed with good reviews and endorphins from his openly salacious camp flirtation with Erika Krouse. By the way she lists Boulder as her home. Wallace was followed by Alan Shapiro (also unrecognizable from his photo) who read new poems about his aging Jewish parents and his cancer stricken siblings. Suddenly, instead of Shapiro’s sister and brother-in-law, it was the two of us who were being described having sex on your fiftieth birthday. Like her, I was bald and drunk on Adriamyacin and morphine. It was as if I had walked into a high school health class to find that someone had secretly videotaped the worst moments of my sex life for the instructional film strip.

Susan Schmidt, the woman sitting next to me, must have felt Shapiro’s poem pierce my body because she intuitively put her arm around me. I only know Susan from reading her workshop submission. She writes of sailing in the ocean, of her Quaker faith in synchronicity, and quotes a poem by, of all people, Kenneth Boulding. I have not told Susan that my fifteen- year-old son, Eben, is sailing the ocean for the first time with Kenneth Boulding’s granddaughter, Meredith Graham. So as Susan, whom I only know through twenty-five brine-laden pages, comforted me through Shapiro’s poetic narrative, I imagined that our normally land-locked son is writing his own poem on Meredith’s body, while lying on the deck of a boat in the Atlantic ocean under the watchful eyes of a billion stars.

I’ve decided one purpose of Bread Loaf is to remind writers that we are all sailing in the same small boat. Uncertain of which way the wind will blow, we drop our lines, fishing for affirmation, while trying to keep time at bay.

Thursday, August 19, 1999, Birch Cabin at Bread Loaf

Dearest Bob,

This morning I lay awake on my narrow camp bunk counting the remaining nights at Bread Loaf. My body feels as if it is at the break point on this marathon, but my brain is soaring, fearlessly flying higher and higher. If I read half of what I have been stimulated to buy and half of what has been recommended, I would not finish, even if I had a normal life span instead of only borrowed time. If nothing else, these weeks at Bread Loaf have been a sobering reminder of how time limits literacy.

I have met many unique and talented writers here–some in person and some only through their public readings, others through both. The women in my nonfiction workshop have the instant intimacy that small group membership confers, even though we have very different interests and backgrounds. Tomorrow our ability to be helpful will be sorely tested. Sundance, isolated by gender and generation, will be the last in our workshop group to have his writing discussed.

We workshop participants have a universally dazed look after our written submission has been critiqued-–as if we had learned to ride a bike and were showing off our “look-no-hands-confidence,” only to suddenly crash in front of our friends and teachers. We pull ourselves and our bicycles upright, trying not to cry, while silently yelping from the searing pain of newly scrapped skin. I suspect some of us will depart Bread Loaf without the dreams of fast riding and writing that we carried with us to camp.

My nonfiction workshop leader is Patricia Hampl. In an idealized world, I would like to enter Hampl’s personal university and study for two degrees–a doctorate in English language and a masters in personal dignity and carriage. She has an exquisite ear and eye for language. It has to be torture for her to wade through our awkward assemblage of effort. Revealing little, Hampl’s neutrality is slightly unnerving. Metaphorically, she is Switzerland at the height of World War II while we are ambivalent allies making use of her to hold our projections, our riches and our secret synaptic sins.

I was very happy to be assigned to Hampl’s group, even more so when I discovered there was a bonus surprise. Helen Fremont, the author of After A Long Silence, is a Bread Loaf Fellow assigned to assist Hampl. There was no mention of this paired structure in any of the pre-camp literature, so I was delighted to find Fremont in our group. I arrived at Bread Loaf the day after we walked the cemeteries of Wappingers Falls in search of the stone marking the grave of the grandfather I never met and find the author whose story started my search.

There is more. Helen Fremont could be Henry Smokler’s sister; Charlotte her mother. Not only do they have the same large and luminous eyes and mannerisms; they also have the same curious minds. More importantly, both of their families came from the same street in Lvov. A serendipitous coincidence or true synchronicity? I asked Fremont to sign a copy of After A Long Silence for Charlotte. Perhaps Helen’s presence is why the fates conspired to give me this gift of brain bread and distance and you the “virgin time” of minding Marley, home, and wilting garden all alone.

Today I had what is listed on the Bread Loaf program as my “publishing consult.” I met with Carol Houck Smith, Senior Editor at Large for W.W. Norton. Coincidentally, Carol is the editor for Stanley Kunitz, who was Uncle Ed’s roommate at Harvard. Also, she is a serious gambler when it comes to longevity. In 1993, when Kunitz was eighty-seven, she signed him to a three-book contract! She didn’t even flinch when she learned I had metastatic breast cancer. Instead she excited to learn that was born in Utah and had never lived further east than Boulder. Apparently she loves stories about the west. Learning that I had been a life-long diarist, she said: “That is wonderful! I think you have the beginning and the middle (i.e., my nonfiction workshop submission “Blackie and Snowball and the Great Fried Egg War” and my Bakeless submission, “My Book of Ruth”). Now all you have to do is live long enough to write an ending!”

I like Carol Houck Smith very much, especially her forthrightness about mortality. She apparently hates “memoirs” and thinks there is a terrible dearth of well-documented autobiographies. Learning that I was an excommunicated Mormon, she said: “Hopefully, that puts you in the perfect position to explain Mormonism.”

At the conclusion of our meeting, she sent me to meet Alane Salierno Mason, who has just joined W.W. Norton, telling me, while laughing, “If we both die, Alane can take-over.”

The first thing Alane said was: “I don’t mind working with agentless authors because I had good mothering!” I felt as if I had been struck by lightning.

The readings and lectures continue to be rich, stimulating and dream disturbing. My mind goes to bed banquet-full and takes hours to settle. Birch Cabin, which seems to be made of birch bark, is an echo chamber for every door, water, and voice sound. I fall asleep late and wake early, in part because I share an adjoining wall with a member of the choral, an eighty-eight-year-old man dedicated to the rehearsal form. This morning I woke to a dream which contained my second lesson on the purpose of Bread Loaf.

It was late afternoon; the sun was out just after a rain storm. My back to the West and warmed by the sun, I stood outside of Bread Loaf’s Little Theater observing a scene through the screen door where all the lectures and readings take place. Inside, in the dim light, there were only a few audience members–six or seven in a theater which seats three hundred. At the podium were twice that number of participant presenters. They were simultaneously exhorting the scattered audience to follow their lines, to respond as if they understood and could affirm what the presenters had written and were reading. I saw writers at that moment as apprentices to the art of strip tease; some shyly, some brazenly revealing the wounds and delights of their lives. The audience members looked back without interest as if they were listless sullen high school students waiting to be released from class.

As soon as I woke up, I started laughing at the dream scene–not disdainfully, but amused by the universal need we writers have to be heard. A desire which, the dream reminds me, is twice as great as our desire to listen.