REMEMBERING LISA WARREN JOHNSON June 7, 1944 to April 12, 2018

Lisa on her Wedding Day, May 1976

I doubt I will ever walk through a garden again without thinking of Lisa. Her death on April 12, 2018 was not revealed until her obituary was finally published in the Boulder Daily Camera on June 21. That morning I wept for hours. The date of her death meant Lisa had not been able to finish her spring gardening, a task she looked forward to and savored every year. I subsequently learned that Lisa had a massive stroke in her sleep and died in the hospital three days later. For many years Lisa had been working for a family who lived nearby as a nanny and tutor for their son. When Lisa didn’t arrive on time on the morning of April 9, the boy walked to her house. When there was no answer, Lisa’s student called his father, who came, entered the house, and, finding Lisa unconscious in bed, called 911. Once we leave our childhood homes, the absence of a spouse or roommate leaves us more vulnerable to medical emergencies in the middle of the night.

My friendship with Lisa spanned fifty years. It began in June 1969 when Lisa came to my office to interview for a teaching position with Project Head Start. An East coast native born in Worcester, Massachusetts, Lisa had recently graduated from the University of Colorado at Boulder and told me that she wanted to make Boulder her permanent home. My Head Start office was located in a World War II Quonset hut which had been unevenly installed on a weedy parcel of land designated to become a future park on the north side of Canyon Boulevard. Lisa arrived at this primitive site for her interview wearing two-inch heels, a Laura Ashley dress, and white dress gloves. She was conforming to style rules which she had learned as a student at Miss Porter’s School1 in Connecticut, where Jackie Kennedy had also been groomed. Decorum in dress was all but obliterated during the 1960s, so I tried to put Lisa at ease by gently teasing her about her white gloves.

Seven months before Lisa’s interview, the Office of Child Development (OCD) had cancelled the Boulder Valley School District’s grant for Project Head Start after an evaluation determined there was a lack of parental involvement and an inadequate nutrition program. When I arrived from Northern Idaho to manage the transition to a parent-controlled non-profit corporation, the five centers (three in Boulder, one each in Lafayette and Louisville) were located in upscale Protestant churches and food was transported from Boulder Valley school cafeterias to the church classrooms (where ninety percent of it was discarded). Looking for ways the teaching staff could build stronger connections with the families of Head Start children and increase parental involvement, I decided to relocate the Boulder centers to low income neighborhoods. Lisa’s energetic enthusiasm led her not only to agree to teach in one of the new experimental centers, but to live in one as well. Luckily for Project Head Start, it turned out that Lisa was more comfortable in polo shirts and hiking shorts than white gloves.

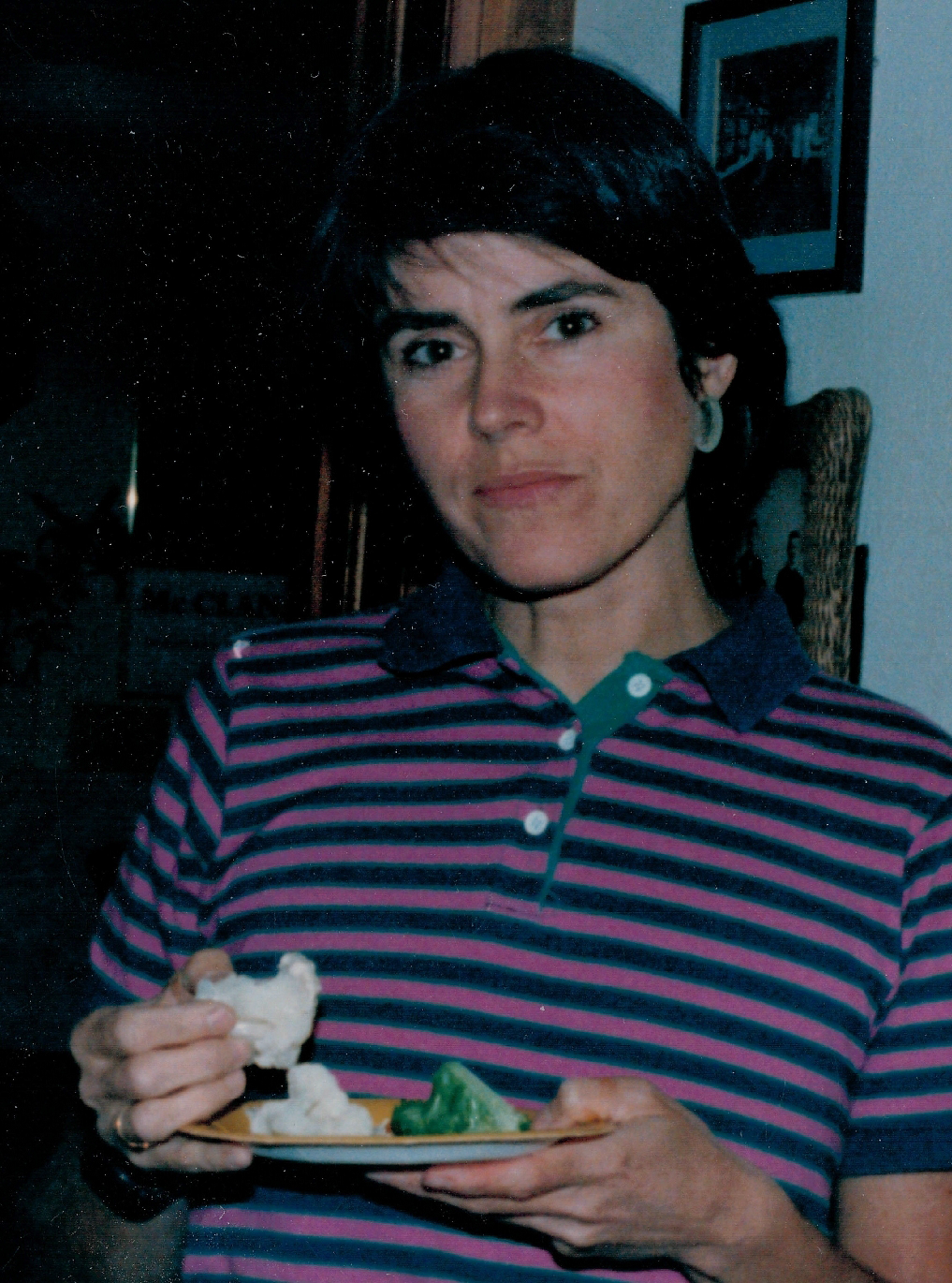

Lisa in Her Preferred Costume

Snacking on Raw Vegetables in 1973

Since it was several decades before the gentrification of Boulder began, Lisa was assigned to work and live in the Goss Street Center, where the Goss-Grove neighborhood population was still primarily low income Hispanic and black families. We transformed the main floor of an older Victorian-style house into classrooms and the yard into a playground. The kitchen became a place where fresh food was served in culturally familiar menus. The house had two small attic rooms; one became a bedroom for Lisa, the other a storeroom for supplies. All but two of Lisa’s fifteen Head Start students lived within easy walking distance of the Goss Street Center. This allowed us to use funds previously needed for busing students to hire a cook for each center. Elmira Davis became Lisa’s teacher aide.

From her first day Lisa demonstrated phenomenal teaching skills. Soon many of her students often found their way back to the Goss Street Center after class ended, making Lisa’s role as resident teacher a 24/7 responsibility. The absence of respite was not the only challenge she faced. One day Lisa asked a parent-volunteer to retrieve an item from the attic storeroom.The mother, like most of the other Hispanic parents was a devout Catholic. She must have been snooping when she spotted a packet of birth control pills on the top of Lisa’s bedroom chest of drawers. In 1965 the Supreme Court had given married couples the right to use birth control, but in 1969 millions of unmarried women in 26 states were still being denied hormonal birth control.Further there was considerable controversy about their use among Catholic clergy and parishioners. A major kerfluffle followed, which Lisa managed to survive by using the full array of social graces she learned at Miss Porter’s School.

Lisa was an adventurous traveler. At the end of her first year at Head Start, she asked me to care for her beloved classroom guinea pigs while she went into the wilds. The following summer, the guinea pigs returned to my house, along with a six-toed calico cat named Splotch who also needed room and board while Lisa traveled to Machu Picchu in Peru. Our friendship deepened when Lisa left Head Start to take a teaching position at Upland School, Boulder’s first alternative elementary school, where my daughter became her student.

Eventually Lisa left Upland to take a teaching position at University Hill Elementary, followed by one at Eisenhower Elementary. Over many years I visited each of her spectacular classrooms. From her first year as a teacher, Lisa had an innate sense of what interested young children. She filled her classrooms with her own carefully curated collections of arts and craft materials, instruments and supplies for science experiments, friendly animals, and favorite books. Each learning environment she created was more impressive than the last.

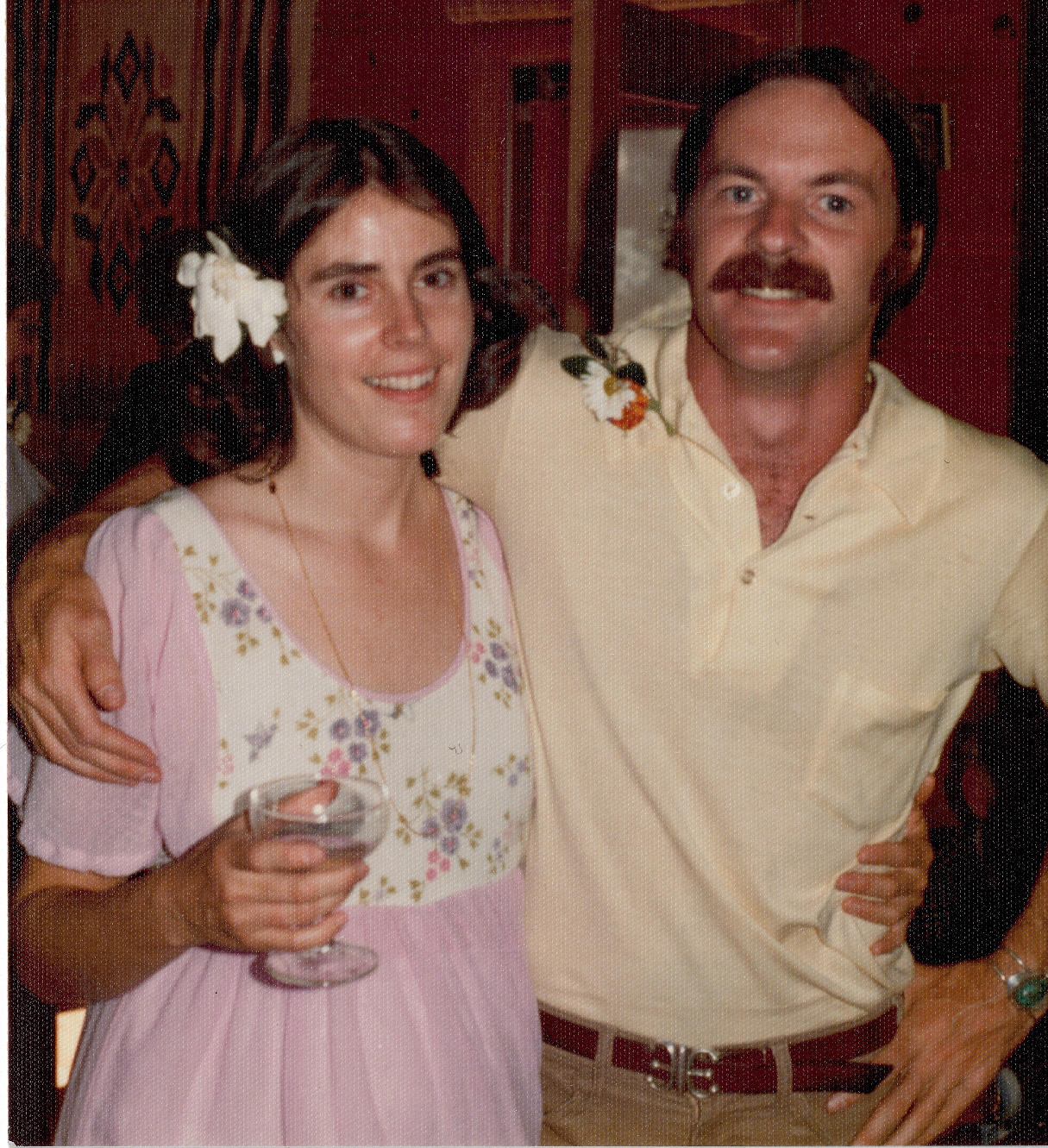

Lisa with her fiance

Steve Kent Clark August 23, 1975

In the fall of 1975, Lisa began making plans for her first and only wedding. She and Steven Kent Clarke were to be married in the spring. I can still see her on her knees planting hundreds of tulip bulbs in a bed bordering the large backyard of her home on 11th Street in anticipation of their May garden wedding.

Lisa’s 11th Street garden was blooming perfection the day before the wedding, but heavy rain began to fall at dawn. By mid-morning, when the rain showed no sign of abating, to make room for the wedding guests, we were forced to hastily remove the bed and other furniture from her main floor master bedroom which overlooked the garden. My husband Bob performed the ceremony. I remember him saying: “Into every marriage a little rain must fall.” More than a little fell that day and on others that followed. In July 1978, Lisa and Steve divorced.

In December 1976, Lisa gave birth to a son, naming him after her father, Alden Porter Johnson. Alden became the primary focus of her life. He was an academic star, as well as an Olympic-level fencer, who graduated from Stanford University. Sadly, after his graduation from Stanford, mental illness and estrangement from Lisa and Steven followed, but Alden remained Lisa’s highest priority until her death.

Lisa with her son Alden F. Johnson

When I gave birth to a late-life son in 1983, Lisa became his personal librarian. Several times a year, Lisa and Alden would arrive at our home bringing copies of their favorite books for Eben. I will always be grateful to her for instilling a love of reading in Eben, just as she did in hundreds of other children who were fortunate to be her students.

Because Lisa shared a birthday with my mother, I found it easy to remember hers. For two decades we had a tradition of celebrating her birthday over lunch. When I began working a sa management consultant, we saw each other less frequently; my travel schedule disrupted easy connections. Luckily, after several years of separation and silence, in May 2015, our paths accidentally crossed at Sturtz and Copeland, Boulder’s gardening center. We caravanned in our Subarus to Vic’s Coffee Shop on North Broadway, where our reunion conversation lasted four hours. A few weeks later, we had lunch on Lisa’s birthday.

We revived our old tradition, doing the same in 2016 and 2017. In early December 2017,Lisa came to my home for tea and holiday lemon cake. That afternoon, Lisa told me a secret story about how she had learned that squirrels have an incredible ability to endure freezing temperatures for long periods of time. Ten days later, Lisa sent me an email.

I just about jumped out of my skin when I saw your book at Boulder Bookstore last week. I grabbed it right off the shelf. I can’t tell you how I’ve loved reading it, especially since I knew many in the cast of characters (including some of the cats), as well as the places and events and some of the story. I did miss reading about Ilona of Hungary, the asparagus fern and Emma Martinez… It’s lucky I still have your fudge recipe on a card in my kitchen drawer because it wasn’t revealed anywhere in the book!

Much Love and Congratulations, Lisa

Lisa Warren Johnson in foreground at

the Boulder Bookstore on Valentine’s

Day 2018 (Lisa is seated next to Patrice

Byrne and in front of Judy Reid,

Richard B. Collins, and Martha Armstrong.)

Regrettably, I didn’t know Valentine’s Day would be my last opportunity to give my dear friend a hug. She surprised me by being in the audience for my reading at the Boulder Bookstore. A few days later she wrote again to tell me that: “I could have been a geneticist in another life!” She went on to explain that Part Two of Optimal Distance had peaked her interest in the new science of epigenetics and that she was diving into the research. She also said that she had enjoyed herself. “I had a long conversation with Patrice after your talk, and a shorter one with Judy Reid who was sitting behind me. I saw many familiar faces from the past who I heard about or met through my connection with you. I enjoyed that part of the evening very much.”

In early June, I emailed Lisa proposing a date and place for her birthday lunch. When she failed to respond, I felt a vague sense of worry. But it has been my experience that most of us become more reclusive as we age. I thought maybe Lisa was treating her blues with chocolate cake from Lucky’s Market, or had gone east to see her siblings, or perhaps was busy reading about human genetics. Sadly, I did not know that she was already gone.

I loved Lisa Warren Johnson – her wonderful laugh; her persistent precision, and how she made our world richer with magical teaching and artistic gardening. I was in awe of herenergetic search for answers in her desire to help Alden, her cross-species relationships with many animals, as well as how eagerly she opened her arms to the most challenging kinds of travel adventures. I will miss her until my last breath. Blessings on her memorable soul.

Joan Carol Lieberman

Boulder, Colorado

July 2018